Lonesome Pine Specials Features Mando Magnificat

By Andrew Adler

Staff Critic, The Courier Journal

Mike Marshall, co-founder of the Modern Mandolin Quartet, quipped last night at the opening concert in this season’s Lonesome Pine Special series, “It’s a mando renaissance”. Judging from the vociferous crowd, he may be right. The MMQ was one of several forces gathered for “Mando Magnificat,” a celebration of the mandolin in its various guises. A sold-out house at the Kentucky Center for the Arts’ Bomhard Theater cheered its heroes and their instruments, which have never garnered the appreciation accorded more “legitimate” tools of the trade.

Never mind that Vivaldi wrote several concertos for the instrument, or that Beethoven composed for it. The mandolin customarily is shunted off into a corner, deemed fit only for informal performances, or for specific (and restricted) color effects In orchestral pieces.

Recently, however, a welcome evolution has occurred. Mandolin virtuosos such as bluegrass legend Bill Monroe have always been with us. But others, typified by Jethro Burns, New Grass Revival’s Sam Bush and Marshall have explored alternatives. The mandolin can now be conceived of as a classical instrument. It is remarkably effective in transcriptions of works composed for more familiar instruments, including the human voice.

Nothing proved this so convincingly as MMQ’s classically based performances. The artists-who besides Marshall included Paul Binkley, John Imholz and Dana Rath-played principally as an analogy of a string quartet two soprano instruments, a mandola (the equivalent of a viola) and a mandocello.

Repertoire ranged from J. S. Bach to Shostakovich, encompassing quartet transcriptions plus arrangements of music written for diverse ensembles. The mandolin is fine at clarifying multiple musical lines: One could revel in MMQ’s gloss on Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins (the opening movement), in which the treble mandolins took the solo parts, with a keyboard reduction of the orchestral part divided between the remaining two instruments.

Similar success accompanied arrangements of quartet movements by Haydn (the “Lark”) and Beethoven (Opus 130), two pieces from Ravel’s “Mother Goose” suite, Debussy’s piano prelude “The Girl with the Flaxen Hair” and the rollicking Polka from Shostakovich’s ballet “The Golden Age.”

Earlier, Bush played an exceptionally challenging medley of tunes, with inspirations as diverse as Monroe and Ellington. The mandolin is usually heard played at hypervelocity, and while Bush’s articulation was amazing, he also impressed with his nuanced dynamics, contrasting vibrato and qualities of plucking.

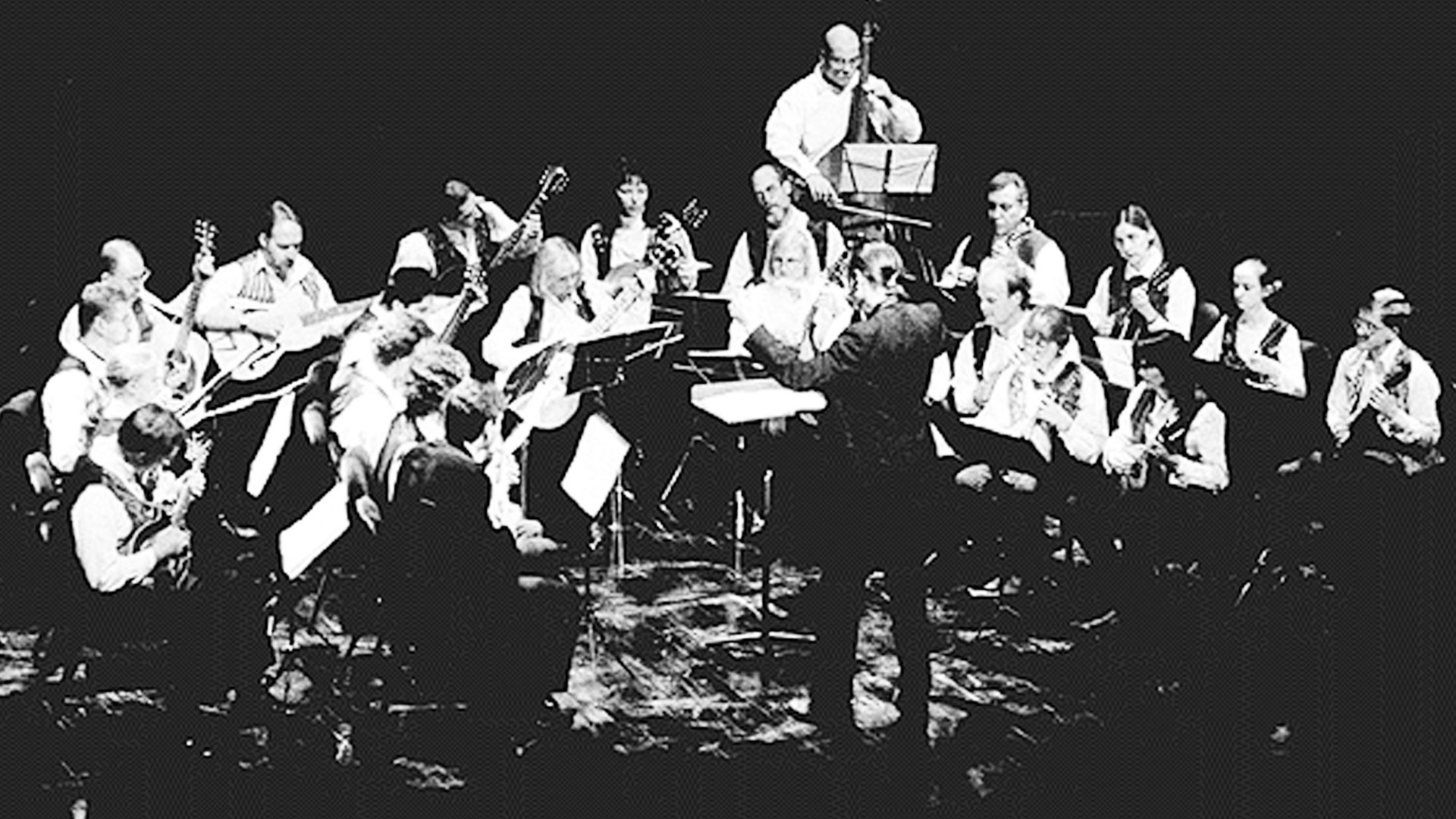

The concert opened with the premiere performance by the Louisville Mandolin Orchestra, a 23-member group conducted by Jim Bates. Comprising mandolins, mandolas, mandocello, guitars and string bass, the orchestra played engaging suites by Elke Tober-Voght and Fried Walter. Though ensemble was some times spotty, the interpretations were consistently skillful and spirited.